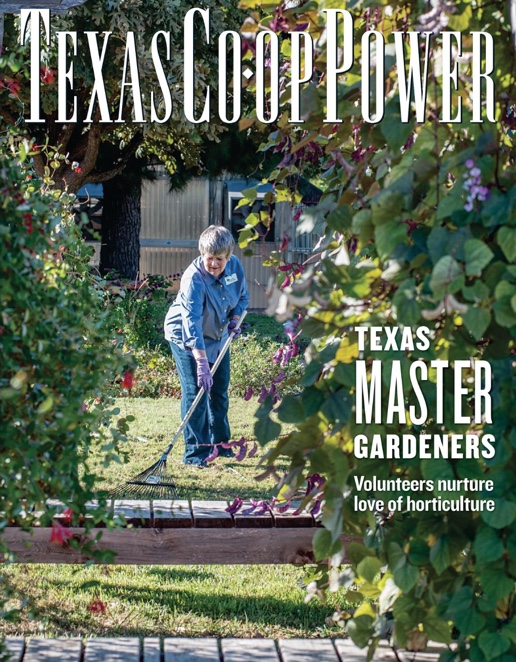

Sly Snakes Sneak Past Defenses in Brazos

Substations, Bringing Down Power to

United Members and Others Statewide.

by

JOHN DAVIS

omehow, the invader slithered right through substation defenses.

omehow, the invader slithered right through substation defenses.

Why it climbed so high, it’s hard to know for sure. It wasn’t looking for trouble, but it found it by accident.

Why it climbed so high, it’s hard to know for sure. It wasn’t looking for trouble, but it found it by accident.

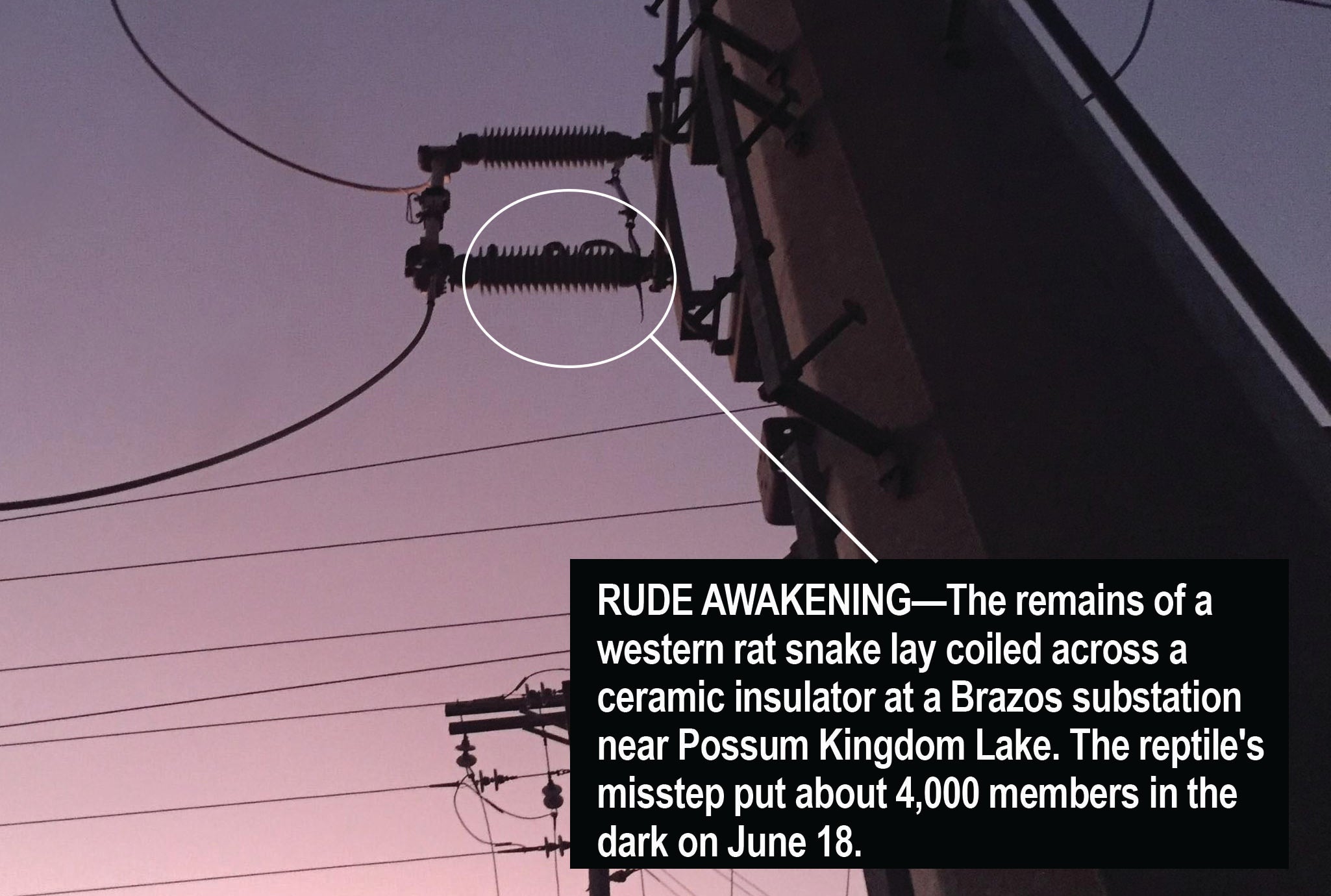

Ben Perry, a journeyman lineman at United’s Possum Kingdom Lake office, remembered arriving at about 5 a.m. on June 18 and meeting a Brazos Electric Power Cooperative employee at the gates of one of their substations that feeds United members.

The sun had risen slightly in the east, and the skies around Possum Kingdom Lake began shifting to a pink that faded into a waning purple night. Just an ordinary morning.

That is, except for the invader and the chaos it had created. About 4,250 United members weren’t pleased to start their day without power. This would turn out to be the third invasion in about as many weeks that United members would face.

Perry said he and the Brazos employee swung their flashlights across the substation infrastructure looking for evidence of why it had tripped off. Surely something big must have blown. Perry imagined, at first, the problem would be visually apparent as the beams of their flashlights probed the shadows.

Yet, nothing stood out.

That is until their flashlight beams came together at once on a ceramic insulator on a switch about 15 feet above their heads. The remains of a four-foot rat snake lay lifeless with its tail dangling over the edge.

“When we saw that, we knew that’s the problem right there,” Perry said. “We could see where the snake’s body had tracked across the insulator and made an arc. I went back to the truck, got a hotstick and knocked it off there.”

The perimeters of Brazos’ substations are protected from natural invasion by an electrically charged metal grid called a “snake fence.”

These devices present an electrical deterrent against invading creatures, though some tenacious animals may find ways to circumvent them.

In some cases, when a phalanx of these invaders land on the snake fence at once, it can cause a drop in its voltage and allow other animals to overcome it.

“We walked around the interior of that snake fence to see if anything was laying on it,” he said. “We couldn’t find anything. The guy from Brazos checked the line, and he found that the line was fully charged.

“We don’t know how that snake got in there.”

Later, as they set about trying to get the substation back online, Perry said the men discovered a tiny bird’s nest hidden from view within close proximity of the rat snake’s final resting place.

Perhaps the snake had followed its forked tongue to find breakfast and found high voltage instead, Perry said.

Statewide Invasion Ruben Padilla is a supervisor of operations coordinator for Brazos.

Ruben Padilla is a supervisor of operations coordinator for Brazos.

While snakes happen every year, this year’s number of infiltrators has been unusually high throughout their service territory, which serves North Texas, parts of Central Texas, as well as eastern parts of the Panhandle.

Most of the substation culprits appear to be rat snakes as well, he said.

“A week or two ago, Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative, located in Bastrop, called me, and they were asking me what we did for snake guards,” Padilla said in mid-June. “They’ve been having a slew of them. Same thing with Lower Colorado River Authority. Everybody is having the same problem we are. As a comparison, if you looked at 2018, we had 19 total outages related to snakes. As of now in 2019, we’ve got 37. That’s almost double what we had for the whole year last year. We’ve never seen this many snake outages to-date in June before, according to our database.”

While he didn’t know what was causing this year’s high numbers, Padilla said he believed the cooler temperatures and rain might play a role, though he wasn’t sure.

“You know, once it starts heating up, it typically stops,” he said of years past. “But when it gets a little cooler, the snakes are out and about. It’s also that time of year when the birds are nesting. We try very hard to keep that under control, but man, it’s impossible to find every nest.”

One thing is for sure, Padilla said, authorities at Brazos and other electric providers are taking the invasion seriously and trying to decide the best solution to keeping sneaky slitherers out of substations.

Already, Brazos employees have increased the number of patrols of each substation and added patrols at the end of each week to ensure wildlife deterrents are working correctly.

According to United’s data, members experienced nine snake-related outages last year, and had already experienced 21 by June 2019.

That is one fewer snake-related outages compared to the 22 total counted in both 2014 and 2012.

The Nature of a Natural Climber

Mark Pyle is the president of the Dallas-Fort Worth Herpetological Society, creator of the Facebook page, What kind of snake is this? North Texas, and a United member based in Granbury.

He said that he wasn’t surprised to hear rat snakes were often found high in substation infrastructure, as they are accomplished climbers.

“Rat snakes are notorious for getting into something you’d never think they would get in,” he said. “From someone who’s a keeper of snakes, I’ll tell you it’s exponentially more difficult to keep them out of something because it’s hard enough to keep them in something. Rat snakes are very beneficial, and you kind of want them around because they are going to be taking up resources that a rattlesnake or copperhead would want. They are positive in most cases. But for a substation, they’re not the best thing to have around.”

Pyle said western rat snakes are the most common rat snakes in the area, although less common Great Plains rat snakes also live in North Texas. The animals seem to have adapted to humans very well, as humans can attract rodents and birds to their properties, which the snakes enjoy eating.

Substations may be attracting the animals because they offer warmth, which the cold-blooded animals require to function correctly, and food in the form of small rodents and birds.

Pyle said he didn’t think there was a larger snake population this year. Last year was dry and hot, and those conditions make snake survival difficult.

“I’ve heard a lot of people say in May, ‘We’re getting good rains in spring. We’re getting more snakes with all this rain.’ Well, sorta, but not really. The snakes come out in the spring, and they start looking for food and mates. Typically, they’re out in times of the day that people like, and that puts people and snakes out together at the same time. They like it about 80 degrees outside when it’s nice and sunny out. That is typically when people come out, too. If it’s flooding, that might displace some of those snakes as well. So people may see more snakes, but they’re always there.”

Once temperatures climb into the 90s and above, Pyle said the snakes become nocturnal and hunt at night. People may see fewer snakes because the animals are waiting for nightfall. Once the sun sets, they may seek out heat sources then to warm their bodies, and substations are typically warm places.

“I wish I could give you an exact answer as to why,” Pyle said. “I can give you some possibilities. Maybe there does seem to be more snakes, but I don’t really know anyone documenting that. The other thing, if the snake fence isn’t deterring some of them, they may be learning how to get inside without touching the fence. If one rat snake can learn, maybe a few more of them learn to avoid it. And then, over time, maybe there are a exponentially a lot more that eventually figure it out.”